Optimising Projection Angles, with Cliffs

A gun fires a shell with velocity \(v\) at an angle \(\theta\) to the horizontal. What is launch angle maximising the horizontal distance travelled?

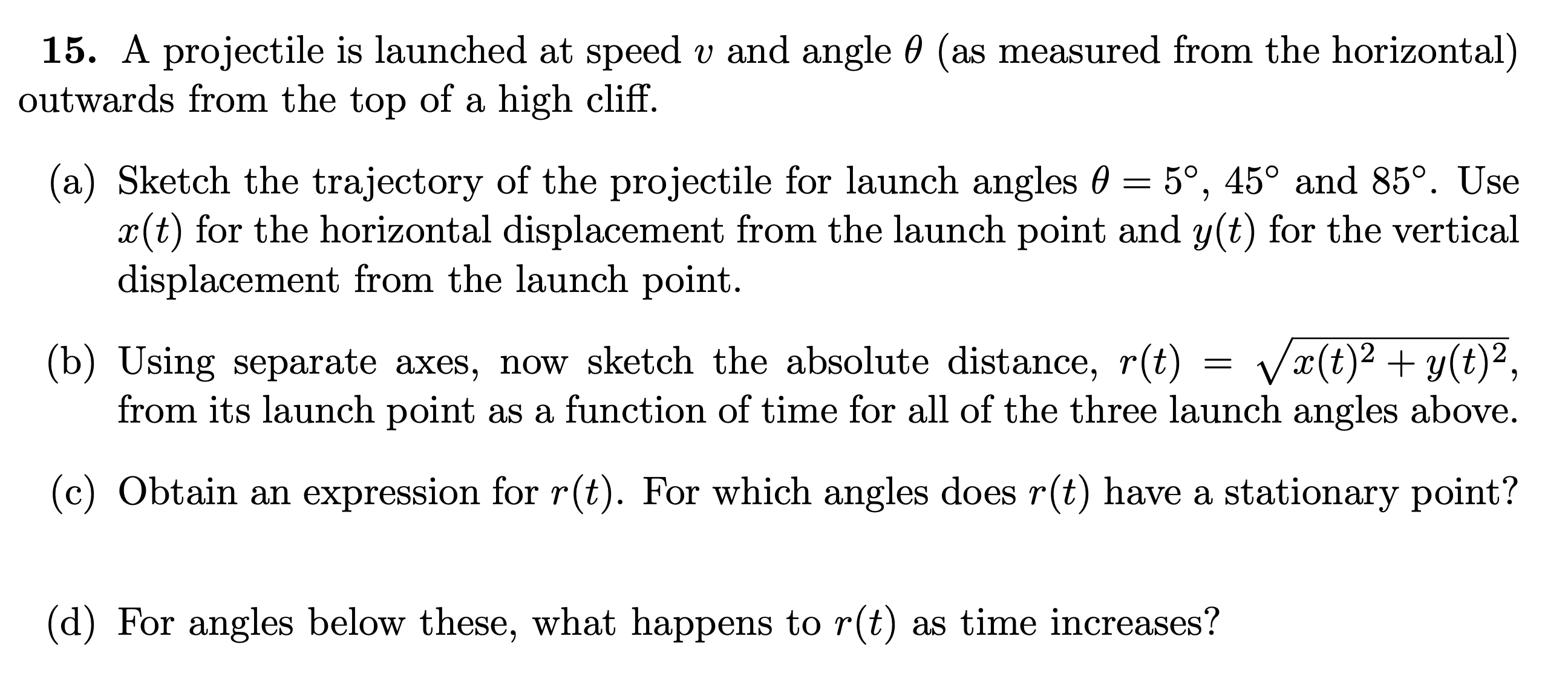

This is a common question, which every physics student does at some point when first learning classical mechanics. I teach it to first years, and vaguely remember doing some variant of it during my undergraduate degree. Once you do enough classic physics problems, they form something like a trope, which you recall when doing unseen ones. And so, when going through the 2022 PAT exam with one of my students last summer, Question 15 (a) struck me as an interesting variation of the common projectile physics trope:

Having never previously considered the angle problem for a projectile launched off a cliff, I became curious if the optimal angle would change. In the original case, it is 45 degrees, but intuitively it didn’t’t seem it’d be the same with a cliff. Say you’re standing on one, throwing a stone into the sea: with a massive height difference between the points of throwing and landing, a larger component of horizontal velocity seems to make more of a difference than the little air time you’d gain from a larger vertical component. So as the initial height increases, we’d expect the optimal angle to tend towards zero. It turns out this problem can still be solved to give a simple formula, and the solution is straightforward, though tedious, yet satisfying. Inspired by Q15, I’ve reformulated the optimal angle problem as follows:

A gun fires a shell with fixed speed at the muzzle of \(v\) \(ms^{-1}\), at an angle of elevation \(\theta\) which can be varied. The shell explodes on impact with the ground, which is horizontal. The gun is positioned at a height \(H\) relative to the ground. Find the optimal angle \(\theta_{H}\) required for a maximum horizontal distance \(x_f\) travelled by the shell, as a function of \(H\) and \(v\).

To do this question, we will use SUVAT to model the motion of the projectile in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, with \(t\) as a parameter:

\[\begin{aligned} x(t, \theta) &= v_x t & y(t, \theta) &= v_y t - \frac{1}{2} g t^2 \nonumber \\ &= v \cos \theta \cdot t & &= v \sin \theta \cdot t - \frac{1}{2} g t^2 \nonumber \end{aligned}\]We can substitute one into the other to get \(y\) as a function of \(x, \theta\):

\[y(x, \theta) = x \tan \theta - \frac{g x^2 }{2 v^2} \sec ^2 \theta. \nonumber\]The projectile starts at height \(H\), however it’s easier to position the origin of the coordinate system at this height. So upon impact, the \(y\)-coordinate is \(-H\):

\[-H = x_f \tan \theta - \frac{g x_f^2 }{2 v^2} \sec ^2 \theta. \nonumber\]We will solve for \(x\) as a general function of \(y, \theta\) first. To do this, we rearrange the expression for \(y(x, \theta)\) and solve the quadratic:

\[x^2 - x \cdot \frac{2v^2}{g} \sin \theta \cos \theta + \frac{2v^2 y}{g} \cos^2 \theta = 0.\]As you can see, the algebra gets nasty here - time to roll up our sleeves, grind our teeth and use the quadratic formula:

\[\begin{aligned} x &= \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{2v^2}{g} \sin \theta \cos \theta \pm \sqrt{\left(\frac{2v^2}{g} \right)^2 \sin^2 \theta \cos^2 \theta - \frac{8v^2y}{g} \cos^2 \theta } \right) \nonumber \\ &= \frac{v^2 \cos\theta}{g} \left( \sin \theta \pm \sqrt{ \sin^2 \theta - \frac{2gy}{v^2} } \right). \nonumber \end{aligned}\]This is the horizontal distance as a function of vertical distance and angle along the trajectory. Now, let’s substitute \(y = -H\), \(x = x_f\) into this equation:

\[x_f = \frac{v^2 \cos\theta}{g} \left( \sin \theta \pm \sqrt{ \sin^2 \theta + \frac{2gH}{v^2} } \right).\]Before proceeding further, let’s re-evaluate - some `sanity checks’ are in order:

- First, the expression inside of the square root is always positive and greater than \(\sin^2 \theta\), so one of the values of \(x_f\) will be negative. This corresponds to a time-reversed motion of the projectile, or equivalently to motion with projection velocity \(-v\)

- If \(H=0\) then the projectile is launched level to the landing, so \(x_f = v^2 \sin 2 \theta / g\) or \(0\). The first solution is maximised at 45 degrees, and the second tells us that the projectile touches the ground at the start of its journey. \(x_f\) behaves like we expect it to, which is good.

Now suppose we hold \(H\) fixed, and wish to find the \(\theta\) that maximises horizontal distance. To do this, we maximise \(x_f\) whilst treating \(H\) as a constant (we use the positive root, since \(x_f > 0\)). Get ready to differentiate:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{d x_f}{d \theta} &= - \frac{v^2 \sin \theta}{g} \left( \sin \theta + \sqrt{ \sin^2 \theta + \frac{2gH}{v^2} } \right) + \frac{v^2 \cos \theta}{g} \left( \cos \theta + \frac{\sin \theta \cos \theta}{\sqrt{ \sin^2 \theta + \frac{2gH}{v^2} }} \right) \nonumber \\ &= 0. \nonumber \end{aligned}\]To make things easier, we will write \(\alpha = 2gH/v^2\). We then divide by \(-v^2/g\), and move the second term to the RHS. After factorising in terms of \(\sin \theta\), \(\cos \theta\), we get:

\[\begin{aligned} \sin^2 \theta \left( 1 + \sqrt{ 1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta } \right) &= \cos^2 \theta \left( 1 + \frac{\sin \theta}{\sqrt{ \sin^2 \theta + \alpha }} \right) \nonumber \\ &= \cos^2 \theta \left( 1 + \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta }} \right) \nonumber \\ &= \cos^2 \theta \left( \frac{1 + \sqrt{ 1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta } }{\sqrt{ 1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta }} \right). \nonumber \end{aligned}\]Which we rearrange to get:

\[\tan^2 \theta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta}}.\]We are not done yet. We square both sides and use the trig identity \(1 + \text{cot}^2 \theta = \text{cosec}^2 \theta\), to get:

\[\begin{aligned} \tan^4 \theta (1 + \alpha \ \text{cosec}^2 \theta ) &= (1 + \alpha) \tan^4 \theta + \alpha \tan^2 \theta \nonumber \\ &= 1. \nonumber \end{aligned}\]Which gives another quadratic:

\[\tan^4 \theta + \left( \frac{\alpha}{1+\alpha} \right) \tan^2 \theta - \frac{1}{1 + \alpha} = 0.\]Solving this one gives two solutions:

\[\tan \theta = \frac{1}{1 + \alpha}, -\frac{1}{2}\]We discard the negative root, finally giving us:

\[\theta_H = \arctan \sqrt{\frac{1}{1 + 2gH/v^2}},\]which for \(H=0\) gives 45 degrees, and as \(H \rightarrow \infty, \theta_H \rightarrow 0\). Nice.

I was genuinely surprised that the solution turned out so simple. The real fun of this question, however, comes from graphing what’s going on. I have done this on Desmos, and you can play around with it by following this link. You can adjust the sliders for the initial height, speed and projection angle, and see how the trajectory of the object changes. The dashed lines represent the initial direction of velocity: grey is the 45 degree projection, whereas purple is the optimal angle for a given \(H, v\). The horizontal blue line marks the maximum \(x_f\), as worked out in the solution above.